BoSacks Speaks Out: Are We Raising a Generation That Cannot Read Us?

By Bob Sacks

Sat, Feb 21, 2026

There is an article titled The U.S. spent $30 billion to ditch textbooks for laptops and tablets: The result is the first generation less cognitively capable than their parents that argues that Gen Z is suffering from diminished literacy, shortened attention spans, and a near reflexive dependence on algorithmic feeds. I remain unconvinced by the panic, but I am not blind to the concern.

My test case sits at my own dinner table.

My grandchildren are wicked smart. The older boys graduated from college with strong grades. One granddaughter is a sophomore at Bard College with straight A’s. The other is a high school junior who can run circles around most adults in a serious conversation about the world around her. They do not resemble the popular caricature of cognitive decline. They read. They think. They argue. They question. They are not zombies scrolling their way into oblivion.

So no, I do not buy the panic wholesale.

But I also do not dismiss the warning.

Because whether the decline is real, exaggerated, or unevenly distributed, the perception of shortened attention and weakened literacy carries real consequences for magazines.

And perception matters.

The Attention Economy Is Not Our Friend

Magazines require sustained focus. That is not a design flaw. It is the product.

Long form narrative. Investigative reporting. Essays that build an argument over thousands of words. These are not snacks. They are meals.

If a meaningful portion of Gen Z genuinely prefers passive, algorithm driven streams like TikTok over deliberate reading, that is not a marketing inconvenience. It is a structural challenge.

Print demands patience. Even a well designed digital long read requires concentration. If cognitive habits tilt toward constant stimulation and frictionless swiping, our core product becomes harder to consume.

That matters more than we often care to admit.

Advertising Follows Attention, Not Nostalgia

For decades, magazines built durable businesses by capturing readers as they entered peak consumption years. Fashion. Travel. Technology. Wellness. Finance. You hooked them early and kept them for life.

If a generation engages less with text heavy content, advertisers notice. They follow behavior. They do not subsidize cultural preservation.

We are already facing declining circulation and sustained pressure on advertising revenue. If literacy erosion compounds that trend, the squeeze tightens. A generation that skims headlines but avoids deep reading is a generation harder to monetize in traditional magazine formats.

There is no sugar coating that.

The Strategic Trap

Here is the irony that should keep publishers awake at night.

In an effort to chase Gen Z, many magazines leaned hard into short video, micro content, scrollable carousels, and social platform mimicry. We told ourselves we were meeting them where they are.

But what if where they are is the problem?

If the very formats we adopted to stay relevant are reinforcing shallow engagement and shortened attention, then we may be feeding the fire we claim to fight.

Magazines once offered an alternative to noise. A curated, edited, finite experience. A beginning, a middle, and an end. A quiet space in a loud world.

If we abandon that identity in favor of algorithmic imitation, we surrender the one advantage we still own. Depth.

The Missing Variable: Parenting

Here is the part that rarely gets discussed.

We talk endlessly about technology. We blame platforms. We criticize algorithms. We wring our hands over screens.

But parenting almost never enters the conversation.

That is a mistake.

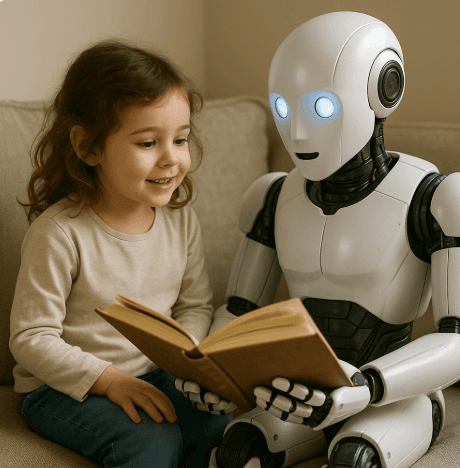

Children do not raise themselves. Attention is not learned by accident. Reading stamina is not innate. It is taught, modeled, and reinforced at home long before it is tested by schools or disrupted by devices.

Parents set norms. They decide whether books matter. They decide whether dinner includes conversation or silence. They decide whether boredom is tolerated or immediately anesthetized with a screen.

Technology did not remove books from living rooms. Adults did.

Technology did not eliminate reading before bed. Adults replaced it.

If a child grows up in a home where no one reads, no one discusses ideas, and no one models sustained focus, blaming TikTok alone is intellectually lazy.

My grandchildren did not develop curiosity by magic. It was encouraged. Reading was normal. Conversation was expected. Questions were welcomed.

That did not happen by accident.

Any serious discussion about generational literacy that ignores parenting is incomplete at best and dishonest at worst.

A Countercurrent Worth Watching

Now for the twist.

Vinyl records are surging among people raised on Spotify. Physical books continue to hold ground against e readers. Younger consumers increasingly gravitate toward tangible objects as a reaction to screen fatigue.

That is not accidental.

When culture becomes frictionless and ephemeral, some people seek weight and permanence. Print magazines sit squarely in that lane. They are tactile. Finite. Curated. They demand focus.

In a distracted culture, that becomes a feature, not a flaw. Am I dreaming? Possibly. But there is evidence worth watching.

If backlash against screen saturation grows, magazines could benefit. Not as mass market utilities, but as premium artifacts. Thoughtful objects. Signals of intent and membership.

That is not fantasy. That is strategy.

The Real Question

The deeper issue is not taste. It is capacity.

If this becomes the first generation measurably less capable of sustained cognitive engagement than its predecessors, building long term readership becomes harder. Not impossible. Harder.

But my grandchildren suggest a more nuanced reality.

The intelligence is there. The curiosity is there. The talent is there. The difference may not be cognitive ability at all. It may be environmental conditioning.

If that is true, magazines still have a choice.

We can adapt downward to the lowest common denominator. Or we can position ourselves as training grounds for deeper thinking.

I know which side of that bet I prefer.

Do not panic. Do not dismiss. Do not blindly chase.

The question is not whether Gen Z can read.

The question is whether parents, publishers, and culture at large will give them something worth slowing down for.

If we do, some of them will come.

And the ones who do will be loyal.