BoSacks Speaks Out: From Modems to Millions – The Accidental Birth of a Newsletter

By Bob Sacks

Mon, Aug 11, 2025

By any modern standard, this newsletter is ancient, practically Paleolithic in internet years. It began not in a Silicon Valley garage or a venture-backed think tank, but in the decidedly analog halls of Ziff-Davis, where I was serving as a production manager in the late 1980s.

Back then, the computer magazines were so hot they practically smoked off the presses. We couldn’t print enough of them. Each issue was a carnival of bound-in inserts, blow-in cards, and creative promotional gimmicks. Then along came a small company with a wild idea: they wanted to attach and eventually insert breakable diskettes, and yes, actual floppy disks, into and onto magazines. This wasn’t the sort of thing you could run through the bindery without creative thinking. It required precision, patience, and a certain tolerance for chaos.

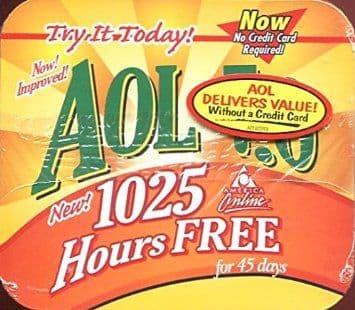

Ziff jobbed me out to coordinate the project. Against all odds, we pulled it off. The reward? America Online, AOL, handed me a free email account. That was no small prize in those days, when getting online meant paying by the hour, listening to your Hayes modem squeal like a tortured fax machine, and praying your phone line wouldn’t drop the connection.

I started “fooling around” with this strange thing called email. The first problem? I had no one to email. Literally no one, except my college roommate, who happened to work in Time Inc.’s Impact Center and had one of those rare, exotic addresses.

For a man who’d been a print publisher since 1972, the idea of sending words over the phone was as intriguing as it was improbable. My roommate and I would exchange notes about magazine production, run lengths, paper stocks, press checks, binding quirks. Soon, a coworker joined in. The list of two became three.

And then, without any master plan, it grew. By 1992, before the web as we know it even existed, I had 1,000 subscribers. No marketing. No ads. Just word of mouth that started in New York City’s publishing circles and gradually went global.

It was the wild frontier, before spam, before SEO, before “content strategy” became an industry. We were just people sharing ideas, troubleshooting problems, and swapping war stories from the printing floor and the editorial trenches. I remain grateful, and yes, nostalgic, for those early AOL years. The sound of a modem handshake still triggers something in me, like the smell of ink on paper. It was a time when the publishing world felt both impossibly large and surprisingly intimate, and when sending a single email felt like an event.

From that modest, dial-up experiment grew the newsletter you’re reading now, a decades-long conversation that’s still going, still global, and still grounded in the belief that this industry, in all its messy glory, is worth talking about.

Postscript: From Hayes Modems to AI Models

In 1980’s, I didn’t know anyone else with an email address. In 2025, I don’t know anyone who isn’t at least partially managed, monitored, or marketed to by artificial intelligence.

The publishing revolution I lived through in the ’90s was about speed, access, and breaking the monopoly of geography. The revolution we’re living through now is about intelligence. artificial or otherwise, and who controls it.

Just as early email leveled the playing field for independent voices, today’s AI tools offer extraordinary opportunities for creation, analysis, and distribution. But they also carry the risk of replacing the very voices they claim to amplify.

Back then, the question was, “Who else even has an email?”

The technology has changed, but the stakes feel eerily familiar. If the modem years taught me anything, it’s that the winners in any media revolution aren’t the ones with the shiniest tools, they’re the ones who know why they’re using them.

And here’s the truth that still works in any era, dial-up or AI: The future doesn’t belong to the fastest or the fanciest. It belongs to the people with something worth saying, and the stamina to keep saying it.

Lessons from the Bindery: What the Machines Taught Me About Media, Meaning, and Mess

Long before newsletters went digital and “content strategy” became a career path, I learned the fundamentals of publishing in the pressroom and in the bindery, where the smell of ink mixed with machine oil and the rhythm of collators sounded like a heartbeat. It wasn’t glamorous. It was loud, mechanical, and often chaotic. But it was honest. And it taught me lessons that still resonate, even as we trade paper jams for server glitches and saddle stitches for swipe gestures.

The first lesson was about precision. In the bindery, everything had to line up, literally. A fraction of a millimeter off, and your trim was crooked, your folios misaligned, your cover askew. But precision alone wasn’t enough. Paper swells. Humidity shifts. Machines hiccup. You had to be flexible, ready to adjust on the fly without losing your cool or your quality. Publishing, like life, rewards those who can adapt without compromising their standards.

I also learned that the last step is the most critical. You can have Pulitzer-grade prose and award-winning design, but if the binding fails, the whole thing falls apart, physically and metaphorically. Execution isn’t just the end of the process; it’s the proof of concept. It’s where intention meets reality, and where the reader decides whether your work holds together or not.

The machines themselves were indifferent. They didn’t care about your deadline or your editorial vision. They’d chew up a cover or misfeed a signature without a second thought. But the operators, those men and women who coaxed beauty from steel and timing belts, were the soul of the operation. They knew the quirks of every press, the temperament of every trimmer. Respecting the craft meant respecting the craftspeople. That’s a lesson I’ve carried into every boardroom and brainstorm since. That and I used to bring two dozen NY bagels to the plant every time I visited.

Complexity was inevitable. Blow-in cards, gatefolds, tip-ins, glued-on diskettes, every job was a puzzle, and the more complicated it got, the more interesting it became to me. Publishing isn’t about avoiding mess. It’s about managing it with grace. The bindery taught me that chaos isn’t the enemy, it’s the medium we work in.

Speed was always part of the equation. We raced the clock, chased deadlines, and lived by the press schedule. But speed without accuracy was a recipe for disaster. A rushed job meant reprints, recalls, and regret. Fast is fine. Right is better. That’s a mantra I’ve repeated more times than I can count, especially in an industry that often confuses urgency with importance.

And finally, I learned that every job is a prototype. No two issues were ever truly the same. Every run taught you something new, about the paper, the ink, the process, the people. Treating each project like a first draft, even if it was your hundredth, kept you sharp. It kept you humble. It kept you curious.

The bindery was my first technologic newsroom, my first classroom, my first proving ground. It taught me that publishing isn’t just about ideas, it’s about execution. It’s about knowing your tools, trusting your team, and embracing the mess. And in a world increasingly run by algorithms and automation, those lessons feel more vital than ever. Because no matter how advanced the technology gets, the real work, the meaningful work, is still done by people who care enough to get it right.