BoSacks Speaks Out: Romance Isn’t Dying. Harlequin Just Got Dumped.

By Bob Sacks

Sat, Feb 14, 2026

Let me start by putting my cards on the table. I am not a book‑publishing insider. That job is already filled, and my friend Jane Friedman does it far better than I ever could. What I am is someone who spends a lot of time on the edges of media businesses, trying to understand a single, persistent question: how content gets sold for a profit, regardless of format, platform, substrate, or genre. Right now, books happen to be one of the clearest places to watch that question play out.

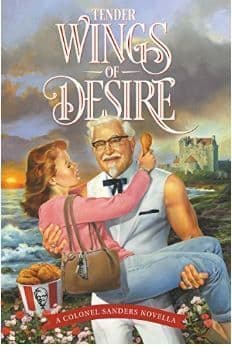

Which is why the news that Harlequin is ending its historical romance line stopped me cold, not because it was shocking, but because it didn’t make immediate sense to me. Historical romance, which I don’t think I have ever read, has always struck me as a sturdy slice of a very sturdy publishing pie. This is not a fragile genre. It has survived wars, recessions, format revolutions, and more regrettable cover designs than anyone needs to revisit.

So, something else had to be going on.

That sent me digging, not to mourn the loss of a category, but to understand what actually broke, who lost leverage, and why a genre that still clearly has readers suddenly stopped working for one of publishing’s most efficient machines.

I probably could have saved myself some time and just asked Jane. We play Catan together most weeks, and I’ll raise the subject at the table soon enough. But for now, here’s my take.

Harlequin Historical will cease publication in fall 2027. According to the article, new submissions are no longer being accepted. Print and digital distribution will wind down across the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. This wasn’t a rumor. It wasn’t a trial balloon. It was a firm decision.

Which leads to the obvious question: why would a giant retreat from a genre that still throws off heat?

Because the story here is not “romance is collapsing.”

The story actually is that “the old publishing machine is losing leverage.”

For decades, Harlequin built one of the most efficient publishing systems ever engineered. Dependable monthly schedules. Reliable tropes. A brand strong enough to outsell individual author names. Distribution that put romance where people actually live, grocery stores, drugstores, and airports. That wasn’t just publishing. That was logistics. Bo, a production guy, loves logistics, and Harlequin was very, very good at logistics.

But the romance discovery engine has moved on.

Apparently, readers no longer browse imprints. They browse emotional promises.

They scroll.

Today’s romance reader is not hunting for a logo on a spine. They are hunting for the hit. The Hating Game. The Unhoneymooners. The Love Hypothesis. The Duke and I. Outlander. Fourth Wing. Yes, I had to look all that up. These books don’t succeed because of who published them. They succeed because they deliver a specific emotional promise, conflict, proximity, obsession, or payoff. If the book lands the feeling and nails the ending, the reader doesn’t care whether it came from Harlequin, a hybrid author, or a self-published series released at warp speed

That’s where I think Harlequin Historical ran into a structural mismatch.

Traditional category lines thrive on predictability. Fixed editorial lanes. Consistent packaging. Steady retail placement. A pipeline that assumes readers will wait their turn. Modern romance thrives on velocity. Rapid release. Algorithmic surfacing. Community recommendation. Fandom momentum.

TikTok’s BookTok doesn’t care what your imprint is.

Amazon doesn’t care what your backlist used to mean.

Kindle Unlimited cares about consumption loops.

Wattpad cares about obsession and shareability.

None of these systems was designed to protect old gatekeepers. They were designed to reward attention.

So when Harlequin ends its historical romance line, it is not announcing the death of historical romance. It is acknowledging, quietly and somewhat painfully, that historical romance has migrated to other production and distribution models, ones Harlequin does not fully control anymore.

Look at where “historical” has already gone.

It has blended into romantasy, where readers get castles, courts, and costumes with magic added, and nobody asks permission from a traditional category shelf. Think A Court of Thorns and Roses or Fourth Wing: courtly power dynamics, inherited status, and romantic stakes that would feel perfectly at home in historical romance, just with dragons and spells layered on top. (Yes, I had to look that up, too.)

It has splintered into trope‑first series released quickly, priced strategically, and fed directly into subscription reading habits, Kindle Unlimited being the obvious engine here. Enemies‑to‑lovers, marriage of convenience, forbidden attraction: the packaging changed, the emotional contract did not.

And it has exploded into sub‑niches that older category structures never packaged cleanly, feminist and revisionist takes like Courtney Milan or Evie Dunmore, alternative histories in the Bridgerton mold, and cross‑genre hybrids that would have made a 1990s line editor clutch their pearls. (Yes, I had to look those titles up, too.)

In other words, the audience is still there.

The audience just arrives through different on‑ramps.

Harlequin itself has been signaling this shift for years, shrinking physical distribution, narrowing focus, tightening the machine. That’s what large legacy systems do when the ground moves beneath them. They try to preserve the apparatus by tightening the bolts. Eventually, the numbers do what numbers always do. They end the argument.

This is not a genre crisis.

It is a power shift.

Romance readers now function as discovery infrastructure. They decide what rises, what sinks, what trends, what sells. They do it publicly, socially, and at a speed quarterly publishing calendars cannot touch. The community layer has become the marketing department. The algorithm has become the merchandiser. The binge has become the business model.

Harlequin didn’t lose because romance weakened.

Harlequin lost because romance outgrew the fence.

And if you’re a magazine publisher reading this and thinking, That’s nice, Bo, but I publish ink and paper, here’s your translation.

Harlequin is a case study in what happens when your distribution advantage disappears and your brand structure no longer maps to how audiences discover and buy. Magazines are feeling the same pressure. Racks shrink. Search referrals decay. Social platforms wobble. Newsstands, home delivery, and predictable ad bundles, the channels that once made you dominant, are no longer yours, and they no longer behave.

We’ve already seen what adaptation looks like. Some titles didn’t try to save the old funnel; they built new ones.

The New York Times didn’t just protect the paper, it built Wirecutter, Cooking, Games, and bundles that turn readers into members.

The Financial Times leaned into premium utility and habit, not volume, and priced accordingly.

New York Magazine turned verticals like Strategist and Vulture into destination brands that travel far beyond the print issue.

Even smaller or newer players skipped the rack entirely, newsletters, podcasts, memberships, limited‑run print objects that feel collectible instead of disposable.

That’s the shift Harlequin missed.

Not demand. Not audience.

Pathways.

The takeaway isn’t panic.

The takeaway is leverage.

Build direct audience. Build membership. Build premium print value that earns its shelf space. Own your data. Package your promise clearly. Stop assuming the market will wait politely for your issue date, your ad cycle, or your legacy cadence.

Because the hard truth is this: your reader didn’t stop loving what you do.

They just stopped finding it where you left it.

And if you want a romance-worthy ending, here it is.

The heroine didn’t disappear.

She didn’t meet a tragic end.

She simply stopped waiting to be chosen.